Today, Betsy is speaking with Stephen Diorio, a renowned RevOps expert, and author of the book “Revenue Operations: The 21st Century Commercial Model.” Join us as they discuss the most pressing topics in the world of Rev-Tech, including customer data fragmentation, the importance of data monetization, and the challenges of managing tech debt.

Guest Bio: Stephen is an established authority in commercial transformation, sales and marketing performance management, and Revenue Operations, having helped over 100 organizations to reengineer their revenue operations to accelerate growth and become more data-driven, digital, and accountable.

Over the last 30 years, Stephen has helped over 100 leading brands – including Armstrong, American Express, CBS, DuPont, IBM, Janus, Morgan Stanley, PwC, Ricoh, SunTrust Bank, Staples, UPS, and US Bank – to reengineer their commercial strategies, technology portfolios, and revenue operations to accelerate growth and become more data-driven, digital, and accountable.

He has authored over 25 research publications and books that connect growth investment to firm value, including Revenue Operations: A New Way to Align Sales and Marketing, Monetize Data, and Ignite Growth (Wiley, 2022), Beyond “e“: 12 Ways Technology Will Transform Sales & Marketing Strategy (McGraw-Hill, 2002).

Subscribe and listen to the Rev-Tech Revolution podcast series on:

|

|

|

| Spotify | Apple Podcasts | iHeart Radio |

Prefer reading over listening? We got you covered!

Announcer: Welcome to another episode of the Rev-Tech Revolution. Today, Betsy is speaking with Stephen Diorio, a renowned RevOps expert, and author of the book Revenue Operations, the 21st Century commercial model. Join us as they discuss the most pressing topics in the world of RevTech, including customer data fragmentation, the importance of data monetization, and the challenges of managing tech debt. All of this and more right now on the Rev-Tech Revolution.

Betsy Peters: Well, welcome Stephen to the Rev-Tech Revolution. We are just thrilled to have you on the podcast and thank you so much for making some time for us.

Stephen Diorio: Thanks for having me.

Betsy Peters: Absolutely. We’d love to get started by just having you give us context about how you got here so how the work you’ve done throughout your career has led you to revenue operations.

Stephen Diorio: That’s great. I’m a trained engineer. I grew up in a factory with General Electric. We’ve made millions of refrigerators, MRI equipment, and I learned operations. As an engineer, in the supply chain and operations, continuous process improvement, systems thinking, unit economics all make sense. While there are variabilities, things go wrong, there are hiccups, at the end of the day, the principles of continuous process improvement, Six Sigma can make you much more profitable.

Once I got promoted to corporate sales and marketing, those rules went away. Sales and marketing regard themselves as exceptional in that salespeople are relationship builders, and marketers are magicians who can’t be replaced by ChatGPT or any other technology. I subsequently had a lot of success in the ’80s and ’90s on the back of database marketing, the call center revolution, CRM, and applying systems thinking to the go-to-market process. At first, it was in direct mail, but pretty quickly, when call centers became a channel for GEICO and some other folks, IBM, wyatt.com, we built that, we started to think about unit economics, transaction costs, outcomes of those transactions.

Along came the internet, and that whole notion of migrating transactions down to self-service created the platform for people to start to think about selling the whole go-to-market process as a system. Technology boomed in the ’90s and 2000s. I became the first technology analyst at Gartner who covered sales and marketing technologies, a new buyer. No longer the CTO, no longer the head of IT. But the technology got way, way out in front of the process.

And so my vision or my engineering paradigm of applying systems thinking and process control to the demand chain was a little bit delayed, and maybe it will always be delayed. I wrote a book in 2000 that was about how technology is transforming sales and marketing strategy. It still hasn’t come true. There are just some systemic headwinds to systems thinking and the demand chain.

I believe the two or three recent disruptions … COVID-19 created what we call 4D sellers, digital, data-driven, diverse, and distributed, they have to operate in a systemic way. I think the advent of recurring revenues has focused people on working as a team to build customer lifetime value as opposed to punching out calls faster or acquiring at a higher clip. So I believe in the proliferation of technology and the growing share of technology in the stack over that lifetime. By the way, the beginning of the story, I have a really big head of hair, kind of like a John McEnroe type of thing.

Betsy Peters: We’ll get to that. We have some good dirt we dug up.

Stephen Diorio: And at that point, I’d say about 4% to 5% of go-to-market budget was tech. And that would probably be a direct mail house like Columbia who did something like that. Now it’s most of the operating and capital budget to support growth is in technology and data and the systems that support that.

That’s a big difference. Media has shrunk, content is bigger, the human channels have shrunk. And so I think if you look at where the weight of investment is, and the weight of infrastructure is, technology-enabled selling using a system is critical. And so the whole notion of using a system and having an operating system for growth, I think its day, has finally come. And the evidence is in the fact that this RevOps thing, revenue operations, whatever you call it, is starting to take shape. It’s the fastest-growing job technically in America. And I think we’re at a tipping point here.

So that’s my background. Again, I’m taking an engineer’s view on selling. And I think there’s some interesting things happening that you and I can discuss.

Betsy Peters: Yeah, I think, well, first of all, your background is fascinating. And one of the things that occurred to me as you were going through your background was that I remember back in the Peppers & Rogers day when they came out, that it occurred to me that we were flipping the paradigm from the microeconomic unit of business being the product, to the microeconomic unit of business being the customer. And that CRMs, as they were starting to come out, were oriented that way, where ERPs were oriented towards product.

And so this concept of the unit economics of the customer journey and everything along those lines, when you get into CAC and customer lifetime value ratios or lifetime value of the customer concepts along those lines, they all harken back to what you said you learned in operations, in terms of continuous improvement and Six Sigma, and all of these things can be applied to the customer journey. It’s just a different set of folks and a different locus for your unit economics.

Stephen Diorio: No, I love that perspective. And by the way, Don Peppers was a real gentleman.

Betsy Peters: Yeah, absolutely.

Stephen Diorio: And he really was ahead of his time. But I equate it to, if you think about in the ’80s, when the car quality was a huge issue, and GM was losing all that market share, I remember everyone put up Quality is Job One on the wall of the factory. But until we instituted TQM, total quality management until we pushed that down into our supply chain until we started compensating people on that, and still in that system people process technology, we didn’t move the needle. But those things did.

And I think if you look at industry now, global economics aside, they’ve licked that quality thing by really digging into it. I think we’re at that moment now. There’s no CEO in the world who doesn’t say the customer’s first, but the people process technology that underlie that, and the incentive systems are just starting to get there. I think this whole thing is very barbelled. It reminds me of the ’80s when we were wrestling with this quality revolution.

Betsy Peters: Yeah. No, I can see that, for sure. And I think the idea of where does a, just to use some of the parlance, where does a marketing qualified lead begin and where does it end. And just the experimentation of each step of the journey so that you can actually apply some of these quality procedures on top of it is all stuff that it should be simple at this point because we’ve all been talking about it since the ’80s, but it’s not.

So I’m interested in your take on that. What is it that you’ve experienced over this arc of your career that gets in people’s way? Why aren’t we farther along in this digital transformation?

Stephen Diorio: Let’s break that down. I gave a talk with Robin Matlock, the former CEO of VMware, about the evils of the MQL and the SQL handoff. But I think if you look at what’s going on in the modern corporation when we go in and do a revenue operations assessment, again, if you would believe, and I’ll show you the … We have a report that we can send to your readers, two-thirds of the go-to-market mix is technology-enabled selling channels. That could be channels with blips, or that could be chatbots, self-service internet, whatever you want. If you look at that, the average organization has 20, 30, 40, 50 pieces of technology, many different versions of that on. But the operations that support them are myriad. The average enterprise we run into has 20 or more operating functions supporting that beautiful linear customer journey you talked about.

So the fracture between marketing-qualified lead and sales-qualified lead exists for good and bad reasons. But if you think about those fracture points, if the technology and the stage of the journey is owned by a separating operating function, on an operational level, they’re motivated by KPIs. They’re optimizing to silos of excellence. And call resolution is a valid metric for the person who’s running that call center, but that’s not a good metric for the CEO who’s trying to maximize total account value.

I think one of the things I would pose to anyone in there is, think about the number of operating teams, marketing ops, sales ops, IT, you call it, that are actually supporting this revenue cycle. And if it’s not more than a dozen, then you are far and away best in class. I met one guy in the last month, poor fellow, who’s been given a RevOps title. He has 400 different operations teams and over 50 organizations now reporting to one throat to choke. Maybe he took off too big a bite, but that’s the end state we’re looking at here, and most organizations can’t do that without really breaking something.

So moving from 40 to 30 to 20 to 10 is a good migration, but those fracture points, and specifically you mentioned the MQL, SQL standoff and handoff, and I’m assuming that everyone knows that’s a marketing qualified lead. So then they don’t exist because people are idiots, it’s a structured circular issue. And I think you’ve got at the silos of automation and excellence where everyone’s getting an A in the class they’re taking, but nobody is taking the class of maximizing customer lifetime value.

Betsy Peters: Yeah, yeah. Interesting. And so based on what you know, given all the folks you work with, what are two or three of the reasons that that happens? Yes, there’s structures, but if people really understood the benefit, they could start to make some changes. Especially with digital transformation in COVID, there was like a beautiful golden ticket to be able to do that, so why haven’t more people done it?

Stephen Diorio: Most organizations will go to someone like a big consulting firm and do the organizational redesign. I think you and I talked about, there’s these CXOs, they’re trying to put a dictator on top of the process. And from a messaging standpoint, that’s great, but that’s almost an impossible job. Most people attack this with organizational redesign. And unless you’re a silo buster like Stanley McChrystal, who defeated terrorism by getting the FBI and the Navy and Army to work together, that’s great, and I’ll talk more about that.

But I think the one lever people are afraid to pull is compensation. You can create what is called a common purpose. You’ll see some interviews on our website with the CEO of Avaya. The head of the CEO of AT&T Business, who said, “I’m going to compensate everybody on customer lifetime value.” Now hunters, people in the acquisition business, don’t necessarily like that because they’ve got to wait a long time or they can’t lie anymore and just walk away and have the customer tricked. People in customer satisfaction have never been paid that way before. Even though when the modern go-to-market engine, they’re probably the most important person, and account managers have to basically be midfielders, get compensated on assisting versus winning.

I think that compensation problem and agreeing on what that metric is and paying executives, mid-level managers, and frontline sellers on that metric, that requires a lot of double comp, a lot of leakage, a lot of attrition. Think about that migration, we can talk about that. But I’d say maybe why that common purpose isn’t manifest in a paycheck is a question I’d ask. And there’s a lot of good reasons for that, but that’s something that is very, very doable but disruptive. And I think if you made that hurdle if everyone was compensated on winning the game and not scoring goals, I think you’d see some change happen. And I don’t see that happening in the paycheck in a lot of organizations. And there’s a lot of reasons for that.

Betsy Peters: And just going back to the total quality movement, was there a similar compensation struggle there? Obviously, the hunter situation didn’t exist in that scenario, but what was the cultural vector for change in TQM, and is there a similarity here or not?

Stephen Diorio: I got to tell you something, and the most unsung organization in the world did it, global procurement. Most organizations only do end assembly at the end get point, but they’ve got a supply chain eight levels deep, and there’s a lot of bad stuff that people do. If you compensate people on delivery, they’re going to pork up on inventory. If you compensate people on quality, they’re going to hire a lot of inspectors. We actually forced organizations to deliver just-in-time without inventory, with statistical process control. We rewarded them for that, but we really put them in a noose, saying, “You’ve got to build quality into the process. You’ve got to deliver to my factory. You can’t have buffer inventories because our economics won’t provide it, and we will reward you greatly for delivery on time and high degrees of quality.” Because we understood that a quality failure or failed delivery costs millions of dollars a minutes in my factory, and paying a couple pennies of bonus per part was well, well worth it.

I think the supply chain work I’ve seen great companies do really broke the back of quality at its source, which was deeper in the supply chain. And again, it got rid of a lot of bad habits. I think when you live in a silo, everybody games to their compensation number. They pad their quotas, they sandbag, they discount, they do a lot of things. And I think play as a team and compensating against customer lifetime value is going to pull the bandaid off a lot of those bad habits. And we’ve got to accommodate people during that change.

But I think that’s the analog. The economics, I was buying $50 million of plastic parts. I had hundreds of suppliers in the supply chain, but I was able to jigger those economics to instill everyone had to be TQM certified. They had to send me reports that show that and I’d pay them for it. So I think that’s a good metaphor.

Betsy Peters: Is it accurate to say that you spread out the compensation across the value chain?

Stephen Diorio: Absolutely. And we rewarded what was really creating value, quality, on-time delivery, efficiency. By forcing them to get rid of the buffer interviews, we force them to have a high-quality process. It’s a symptom. If there’s a huge buffer inventory, it’s a bloat on everybody’s balance sheet, but it really is a sign of hiding weakness.

Betsy Peters: Yeah, that makes sense.

Stephen Diorio: To bring it up to our topic, if you think about revenue intelligence, nobody believes the opportunity pipeline. Everyone thinks they’re optimistic, padding, sandbagging, whatever. And people are starting to look at real activity metrics that says, “This opportunity, no one’s even talked to this person in the last six months. How can this still be on the pipeline,” is a symptom of that. Peeling off the bandaid, getting visibility into what matters.

And again, there are no bad guys here. I just think you’re starting to peel back these silos and shine a light on some pretty bad habits.

Betsy Peters: And you’re starting to be able to use data and systems to foreground the things like that matter. Where before it was hard. There was a lot of activity and not an easy way to see it quickly or see where the weaknesses has been.

Stephen Diorio: There’s still a signal-to-noise issue. We think you’re on a good point there, because there’s a lot more signals, a lot more data signals. But I think AI and this revolution, analytics in sales and marketing, really can keep up with it and have to really simplify it finally. So while there’s a lot more information, there’s a lot of mechanisms to manage that information and tease out what matters.

Betsy Peters: Yeah. Well, let’s go there. Let’s talk a little bit about what’s keeping you up at night right now, based on where we are in the evolution of this tech stack, and maybe a little bit about the underlying data or the signal-to-noise ratio.

Stephen Diorio: Yeah, so this is really interesting. What we are hearing from customers is yes, there is a person, some poor sucker who got a revenue operations title. Technically they should manage 13 different functions, analytics, finance, in terms of they should have finance skills, analytics skills, technical skills, planning skills. They should know what it’s like to be a sales manager. The best of them were actually sales reps. And okay, so there’s that one poor fellow who’s got it all, but most people are combining marketing ops and sales ops or aspects of it.

Second, 95% of them in the current economic climate, are being asked to simplify, rationalize, and optimize their stack. And by that, I mean the average organization has just thrown technology at the problem. There are hundreds of overlapping sales and marketing technologies that have formed this stack. A and a couple of dynamics have happened. One, all of the software started to do the same thing. Categories are converging, like the universe. And so if you had a software package that did enablement and training and readiness, three separate software packages, it’s likely that three or four of your software vendors do all those things. The same thing is happening in quota development, planning, resource allocation, so on and so forth.

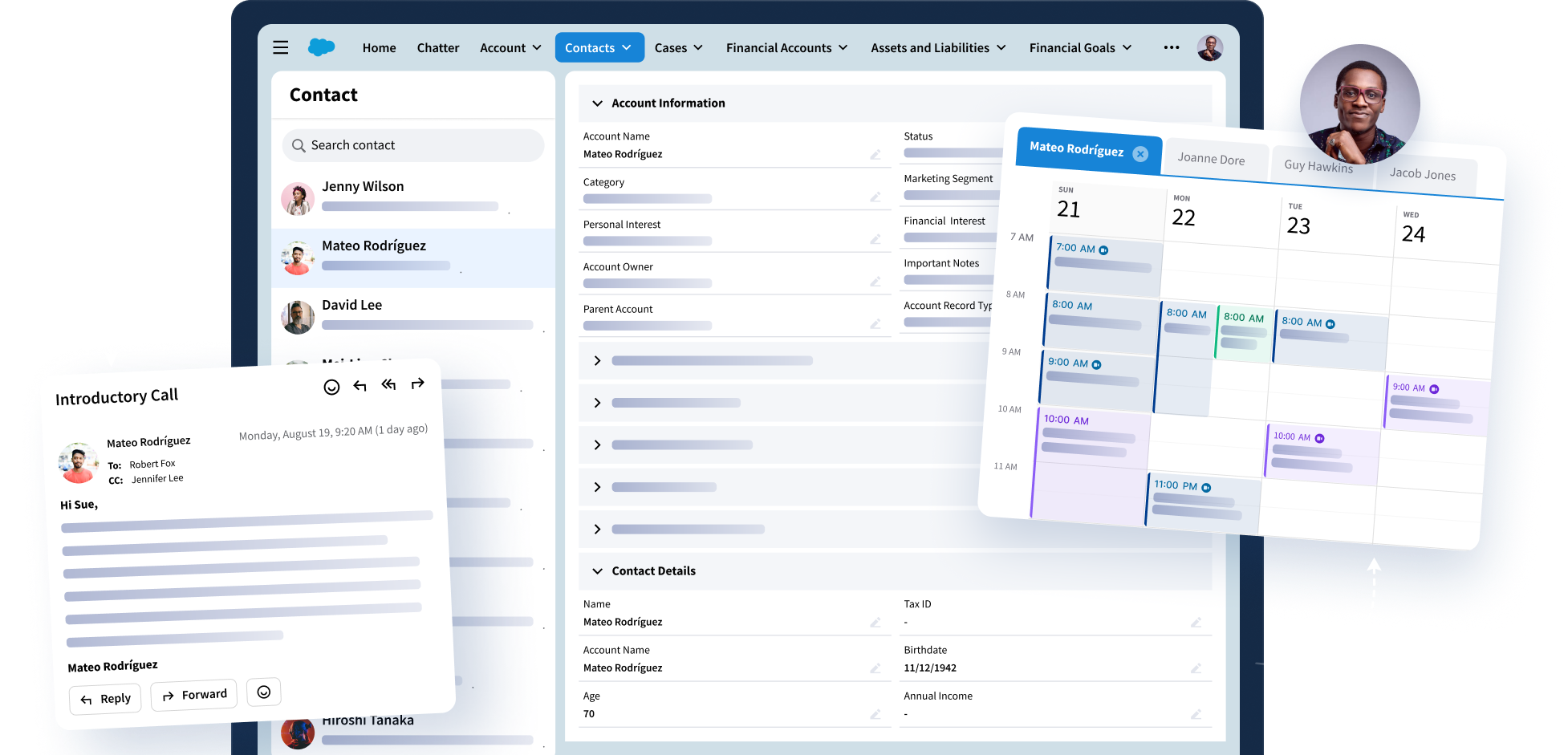

So you’ve got way too many pieces in the stack. They’re increasingly overlapping. Half of them aren’t being used, many of them are making the process more complex than simple. So there’s a very good reason, according to Salesforce, which is good data I think, that 95% of people are looking to simplify the stack, cut the fat, look for redundancies, swap out one platform for three. The smarter ones are trying to simplify the seller experience, create one motion, one pane of glass that are simple.

I think if you’re asking me what conversations I’m having the last two to three months, it’s around that. But it gets to your whole issue of form following function. That’s not so easy. One reason that’s not easy is there’s no blueprint. If you look at a blueprint for rationalizing your tech stack, you’ll see the top 30 tech vendors are all happy to tell you how to build a tech stack around their thing. It’s basically like the Woodrow cartoon of the spark plug vendor going into Detroit and telling people they’ve got the key to re-engineering the internal combustion engine. There is no objective blueprint. We work very, very hard in running our book revenue operations to create an objective and translatable operating system with data in the center. That addresses management’s need for information, pushes personalization information out to the field, enables channels, enables marketing, enables training, enables resource allocation, maximizes margins and personalization.

So if you look at that operating system, at the center of that, people are accumulating data from a variety of sources, first-party data, and third-party data. If you’re in the media world, there’s second-party data that Meta owns. But at the end of the day of the center of the universe, like the sun, is this dataset. I’ll give you a couple tangible examples. If you give me a marketing budget, I would argue that 80 to 90% of that B2B marketing budget, its goal is to drive anonymous interactions to a website. So the marketing people are raising their hands, saying, “I’ve got apps, landing pages, websites, chatbots,” and they’re talking to the customer. In most cases, I don’t know who that customer is, but I’m successful because they’re engaging with my brand.

Over another part of the organization. I got CRM data that has every customer account prospect to persona. If I can marry those two pieces of data together, I can increase the return on my marketing budget 10 to 20-fold because I can de-anonymize these people and let a sales rep know that their customer’s actually on their website and their exhibiting behavior then indicates a cross-sell or an attrition event or some type of signal. So just combining those two data sets, first-party data that I own on my front-end marketing systems and the marketing budgets that drove people there, to the poor salespeople at CRM who are completely divorced from that conversation, marrying those two things together creates enormous value. Now is that easy? No. Should that be a number one, two, or three priority for any RevOps executive? Yes, it’s hard, but not difficult. It takes elbow grease, but the return is there.

I think that’s a great example. Start to color that in. Virtually every selling conversation is recorded these days. And with AI and MQL, I can then mine that information in real-time for signals. I can improve my intent signals. I can use those conversations to handicap when and whether something’s going to close. I can use that to coach my sales rep. So weaving in these information sets, most of which we own, has huge value to recommending the next content, establishing quotas, tightening the sales forecast, providing foresight into leakage and changes. The biggest issue people have is the opportunity forecast may not be accurate, but nobody really knows what that client’s going to look like 24 months after the booking because it’s all depending on usage, adoption, and all sorts of post-booking variables. That data can be used to start to create a better model for lifetime value.

So I know I’m talking a lot, but this notion of a revenue operating system says we own that data, it needs to be managed coherently, and it needs to be allocated to drive outcomes. Whether it’s better pricing, a better piece of content, a happier customer conversation, or a more accurate forecast, or really better defined territories and quotas because they’re all a mess. I don’t care which one of those things they are, the return on investment and the ability to approve the engine is amazing.

I’ve talked a lot about the data, but I think one of the big things that missing is one picture for how that data comes together and when and where I’m going to use it to make this system run better. And for us, that’s what we call the revenue operating system.

Betsy Peters: Yeah, I wanted to cue back to something you said a little bit earlier. You said something like the smart folks are designing it from the sales experience in designing the RevOps system. Did I get that right?

Stephen Diorio: Yes, yes.

Betsy Peters: Yeah. So I’m wondering how many people are doing that and thinking about the data that’s generated at each step in the customer journey and then using that to create requirements for their vendors to find where the gaps in the data are. Because what I find is in my conversations, most of these RevOps folks are getting pounded by every vendor out there in that RevTech analysis that shows a thousand plus vendors.

And so they really just do a head-to-head comparison. and it’s more about systems and their capabilities than, like you said, the design of a sales experience and the requirements that you actually have to gather the data so that you can harness the data and then get to all of these outcomes you’re talking about.

Stephen Diorio: You’re very smart and you’re driving to the fourth level of the problem. Let’s recap our conversation.

First, most executives agree the customer’s first and people are now defining the customer lifecycle appropriately. A funnel that blows out into a bow tie, where most of the action is after the booking and expansion revenues and total net recurring revenues. So that picture’s out there. So the figurehead stage, I’ve named somebody in charge of this, they put a poster on the wall, the customer is first, everybody is responsible for this thing. Now there are flaws, there are silos, and compensation.

The second thing we talked about is if I could just compensate everybody on customer lifetime value, for whatever that means in your organization, recurring revenues, whatever it is, now I’ve moved the needle forward. That’s going to unearth a third layer that you just talked about, the hotspot analysis. You talked earlier about points of failure. The example we talked about was the marketing qualified lead being handed off to sales. That’s just a point of failure. There’s also handing off the booking to the finance people who are going to screw up the forecast. And bills that are generated here are leading to billing, invoicing errors because of changes that we don’t see down there.

So now you’ve got these little explosions along this journey that need to be fixed. And at the bottom of that you’ve got these ops, 40 different operations, 50 different technologies, but the real sin, and you got at it, is that you’re not monetizing that data. And so as I see people start to get smart, they go through that journey, and they’re like, “I want to rationalize my tech stack, I want to eliminate these things.” They quickly realize that they need a unified data model and that the real sin here is that the data is a lot of different places.

And by the way, the data that we’re talking about, the customer interaction data, is the largest financial asset in the business. As evidenced, the customer database at United Airlines is valued at more than the entire company, including the planes and the pilots. So customer data is your largest financial asset, yet no one’s in charge of it. You got someone running your building, you got someone taking care of the airplane, and those are important assets, but they’re fractional compared to the value of customer data.

So I think you’re getting at some really important things. The data fragmentation is the real sin, and the data is the most valuable asset, more than the technology that generates it. And nobody is sitting on top of that except in the most advanced organizations. And even there, there’s the mythology of a single source of truth and this data lake that sucks in all this money. There’s no easy answers there, but I think having somebody own it, value it, and systematically start to harmonize and monetize it is the highest life form. So you really jump to the end game, so Betsy.

And again, I think people have to go through those layers of acknowledging the process exists, acknowledging the fragmentation and failure, getting at simplification, and getting at the data. So it’s the last thing they arrive at, but like you said, it’s the most important thing.

Betsy Peters: Yeah, interesting. Wondering how much you still have a foot in the manufacturing world because there is the concept of data operations. Basically, taking IoT data and information from the manufacturing floor and then normalizing it and curating it and basically doing what you’re talking about for customer data, but they’re doing it on the production side.

Stephen Diorio: I think you’re dead on. And I do have my finger there on a couple of dimensions. One, we wrestled with those manufacturing control systems. We didn’t have the technology in the ’80s and ’90s when I had hair. And I think they mastered that. And they do manage it coherently, and they use that information to make the process from beta. We started to create a market for that information for procurement because we wanted to see those numbers. I mean, there’s only four things that matter in manufacturing, work-in-process, inventory, quality, throughput, and costs. And those variables are all data-driven.

But manufacturing goes further than that. There’s this revolution in SaaS, and everyone is getting all worked up over recurring revenue like it was invented. If you talk to a CFO in a manufacturing company, he’s like, “I’ve been a recurring revenue model for decades. I have these long-term contracts that are based on usage with lots of different moving parts. Do you guys in the software industry think you’ve invented this when you decided to go sell SaaS stuff?” And if I’m Boeing, my formula is really, really complex with a lot of moving parts, usage, layoffs, demand forecasts. So they’re like, “We’re way out in front of this recurring revenue thing, and you guys in the software industry are just figuring this thing out.”

So I think manufacturing is a great metaphor. And in fact, they’re among the fastest-growing markets for some of the more advanced go-to-market technologies.

Betsy Peters: Tell me how you’re advising your clients right now about AI, whether it’s automation type AI or large language models, and the risks that they run with the data gaps. How are people thinking about that right now?

Stephen Diorio: Well, a number of things, and I work with the people a lot smarter than me. I’m a fellow at Wharton Analytics. We actually teach a really great class called AI for Executives. So a couple of things, broad brushstrokes, that I’m just going to say what smart people like Raghuram Iyengar at Wharton will say. One, I think any executive and this is why RevOps is so important, has to understand the math. They don’t need to code, they don’t need to deconstruct the algorithm, but they need to understand how the algorithm works. And the reason that he says that the senior executives need to understand the math, is they have to ask the right questions to the data and they have to question the black box and understand enough to do it.

So the job of the senior executive is to direct the organization. And if you don’t understand enough to know what you can learn from data and what are the right questions to ask of that data, then your whole organization is going to just create what they always do. A thousand different cool Tableau things and dashboards that have a million variables, 999 of which don’t really impact financial value or operations. So that signal from noise problems stems from the fact that senior executives are not asking the right questions.

The second thing that I learned is there is no such thing as perfect data. And like everything in life, like when my wife picked me to marry, she had a lot of imperfect data and probably made a horrible decision, but good for me. At the end of the day, we need to make decisions on imperfect data. The trick is to stop arguing about how bad the data is and start saying, “Well, what conclusions can we draw from that?” And I think the beauty of the RevOps conversation is you’ve got an executive who understands analytics and data but knows how to speak the language of finance and knows enough about the data to dispel any management presentation. Find a spelling error, find a calculation error, question the data, and then the whole presentation goes down the tubes if you wanted to. You need to look past that to say, “What can we learn from this data, what is it telling, and how can we use that to hypotheses in my organization?”

So the second thing I would say is people expect perfect data when they can do a lot with imperfect data. And the third thing is they need an architecture to start with what we call a B2B CDP, or customer data platform, where we start to systematically connect the dots across this data. I mean, there’s some obvious plays. One of the most obvious plays is to take signals I already have on my website and somehow, manually or otherwise, get them to sales reps. And that’s where AI is simplifier. It makes managing data simplifying, it makes writing back what happened in a call simpler, and it makes sifting through all those website interactions to find the ones that salespeople care about, easier.

So it’s the labor-saving device at first, it moves information around, it pulls out signals of intent or intent, or I’m sorry, attrition, that say, “Look, if you got to make five phone calls today, I call these people,” because whatever it is, they’re either pissed off or looking to buy something from your competitor. I think AI can help the ball in those things. It’s not the universal, I don’t even want to get into the ChatGPT thing or any of the issues related to that.

I think if you think about AI as a labor-saving device that sifts through data, imperfect data, pulls out nuggets from that, moves those nuggets to people that matter, make the hygiene of that data work. I can list some really practical and tactical things. Getting your data a little bit better, mapping it to the accounts you’re selling to getting it to the rep who cares about that account. Those are all what we call smart actions or connecting the dots, that move you forward. You’ll never get the perfect data, nor could you operate with perfect data because if so, my wife would be married to Brad Pitt and we’d all be done.

And so I think I hit on four vectors. An executive needs to be smart enough to ask questions to the data. You’ve got to live with messy data. You’ve got to use AI as a labor-saving device to clean, move and contextualize that data. And I think you need an architecture for how it all comes together.

Betsy Peters: I want to move to an area that’s a struggle for a lot of the folks, for us and for a lot of the folks that we talk to, so this trend towards anonymizing the contact. There’s a lot of technology out there that can help you de-anonymize the company, but you don’t sell to buildings, you sell to humans. And so what are you advising your companies on in that regard as we’re starting to lose more and more signals out there, third-party signals, et cetera, on the individual?

Stephen Diorio: So, full disclosure. My company is owned by the biggest and best media agency in the world to rise in media, so we’ve got a front row seat on that. We place media for huge multimillion-dollar media budgets globally. And I think the shorter answer is everyone’s had the cookie debate, everyone’s seeing, if you operate globally, you see this. In Canada, we can’t do what we can do here in the States, much less Europe and other parts of the world. I think the answer is just like exercise, diet and sleeping, you’ve got to move to a hard, persistent identifier. And I think marketing automation and Salesforce are really pushing people that direction.

But unless you have permission, and you do, your salespeople are talking to the people every day and have relationships with people who are opting out of our cookies over here. I think marrying those up allows you to take the goodwill, build a persistent identifiable ID, and then use that as a foundation for personalization versus other things. I mean, at the end of the day, relationships lead to hard IDs. Once you have that hard ID there’s a lot of cool things you can do. For example, people are bringing in third-party intent signals, which are really rich. And if you trust the fact that that’s actually a person you know and you can attach it. Everything in life, the economies of scale in sales and marketing, are not around media buying or rep productivity. They’re around personalization at scale, personalized by locality by the individual. You talked about the costs of versioning content across geographies, personas, stages in the life cycle. Everything else is just huge. Having a persistent ID to anchor those efforts and recommend the right content is critical.

So I think you got to build that right. There’s other people I can refer you to. But what we do with our clients is we use this notion of a customer data platform. We establish a person, like you said, with a face, who we know and we have … When I say a persistent ID, it’s an email address, social security number, phone number, whatever. And then you can lay that up against 10,000 variables and figure out if they’re a fly fisherman, or they like Bonsai or they’re a Cubs fan, and that’s all great. But the easiest way to do that and the most sustainable way to do that is to figure out what that anchor is.

There’s a lot of software firms out there that’ll tell you they have a silver bullet there. But I think at the end of the day you have those relationships, you have those email addresses, you’ve got the first-party data, you got to build that as a foundational pillar.

Betsy Peters: Yeah. No, I think that’s a terrific answer. But your first analogy of it’s like diet and exercise is exactly right because it just takes time. It takes time and diligent.

Stephen Diorio: It’s like my wife, who’s helping my son plan a trip to Japan. I know an actual geographic photographer in Tokyo who knows where all the hotspots are, and an ex-employee knows where all the clubs are. Like why not call those guys up and get that information? Why am I looking at guidebooks and the third-party information to infer?

And I think this is that marketing and sales disconnect. Marketing immediate people want to do that because they don’t know the people, but salespeople and service people, they know them intimately and have that permissioning. So there’s an arbitrage there that is a symptom of this fracturing that we’re talking about that’s easily resolved.

Betsy Peters: Let me shift a little bit and ask you about how many of your clients are wrestling with tech debt and how important that is as they’re trying to make all these other determinations. It’s just dealing with the backlog of things.

Stephen Diorio: We’ll come back to the core statistic, which just reflects all of my conversations. 95% of organizations are trying to rationalize, simplify, and reduce the cost of their tech stacks. Now if you deconstruct that, what is the tech stack? Is it just CRM and a couple of other things? Or my definition, it’s everything that touches the customer. And when they talk about cost, they’re talking about licensing fees.

But I think your notion of tech debt is important. You’ve got adoption costs, the fact that you have duplicate licenses, multiple instances, and then the administrative overhead associated with each one. And that’s like an iceberg. Yeah, I can see the $60 a rep cost and I know that half my reps start using it and that’s a sin. But when I start to look at the operational overhead and administrative overhead in terms of time, data hygiene, manual intensive, maintenance, all of a sudden I’ve got … It’s like a factory. Variable cost and fixed cost, and nobody is adding up the fixed overhead costs.

There’s also just a million smart things to do. Most of the smart executives I talk to saying, “Look, I can connect the knee bone to the thighbone. I connect the know the elbow bone to the arm bone,” whatever. There’s a million smart things to do. Their question is, “What do I do first?” And the reality is, as we talked about, no one really understands the financial value of their data. No one has a rational, financially valid formula for prioritizing project A, connect the knee bone to the thighbone, project B, connect the wrist bone to the arm bone. And the way we do that based on sales productivity, time in front of the customer, it’s failed. Those are bankrupt measures of how to do it. You need to understand their impact on margin, revenue leakage, cashflow and customer experience, risk, and control.

And so the financial models we used to prioritize how to work our way out of this debt. You implied there’s an endless backlog of integration and technology initiatives that can improve the company. The question I’m being asked is, “What do I do first?” And I have a list of six smart actions in my book that are guaranteed to pay off, and they don’t have a huge change management cost to them, and they use existing parts. But whether you use my six or the other 40 that I hear people doing, I think the real issue is people can run a cashflow model as to whether to lease a factory or buy a factory, but they can’t come up with a cashflow model that says, “Project A is going to be much more impactful than project B to our margins, our stock price, and our P&L.”

And so, three aspects of tech debt. One, nobody even knows or counts revenue cost per rep. We see when people do, that the cost of technology and data associated with a rep exceeds $10,000 in many organizations. Now that’s less than a truck driver, an Amazon worker, or even a fast food worker at McDonald’s. That’s a lot of tech. And then no one’s adding the overhead and administrative debt that’s associated with that, so that’s even more. And then no one is prioritizing opportunities to rationalize. There’s a lot of opportunities to take three pieces of the stack, show it to vendors, and say, “Consolidate this for me.” There’s a lot of opportunities to say, “Can you connect the knee bone to the thighbone in an intelligent way to the …” Like what you said, show the picture to your vendors, saying, “What are you going to do to make this simpler?”

And prioritizing those, drawing them, prioritizing those seems to be the number one issue. And it’s not that they don’t have great projects on the board, is they have no financial basis for picking project A or project B. We have something called the Revenue Value Chain, which we built with actually MASB, the marketing ops, a bunch of academics and accountants, that actually the CFO will buy into that then explains why project A would be better than project B in a language that a CFO would understand. And I think that’s a huge cap. There’s no vocabulary here to describe this stuff.

Betsy Peters: Tell us about your book. What prompted you to write the book? What’s the scope of the book, and how can it help some of the practitioners who are listening to us?

Stephen Diorio: Our stock and trade is we talk to the most senior executives we can find about this. When I wrote my first book and when I was a Gartner analyst, I was preaching to the converted. Any operations executive, sales ops knows what they’re doing in their little silo. And what’s happening is that the world is barbelled. The change that has to happen has to come from the top. It’s risky, it requires compensation to be changed, we talked about that. And it requires a warranty. Everyone says, “Oh, it’s okay to fail.” Well, you’ve got to back that up from the top, and it requires control. The only person who controls all the moving parts we’ve discussed in most organizations is the CEO, and of all the organization it’s this new czar.

So how can you ask one or 40 operations people to reach outside? They don’t pay these people. They don’t work for them. They’re not motivated, they’re motivated by different KPIs. You’re asking some operations person to go out amongst their peers and convince people that don’t work for them to take risks and to change, which is the hardest thing in the world. And so they know what to do, but they can’t make it happen. The people at the top who can make it happen aren’t learning enough about what it takes. We talked about it. Change the compensation, prioritize knee bone to thighbone to hip bone initiatives, and put a financial model out and criteria and mandate to change. Just like we did with the suppliers.

So I think the reason I wrote the book is I wrote the book for CEOs and boards because the people in the operating jobs and the people who man the technology know what to do, but they’re not empowered to do it. And it’s almost like a Venus and Mars book. It lets the people on the front line, the operations people, communicate in the language of finance, tied to stock price, and to an executive. And a lot of what we do is bridge that gap.

Betsy Peters: That’s great. And what’s the title of the book?

Stephen Diorio: Oh, it’s called Revenue Operations. I had a much longer title, but my editor at Riley told me to cut it down.

Betsy Peters: What was the ideal title for you?

Stephen Diorio: Oh, God. The 21st Century Commercial Model. But I know myself well enough not to trust myself. And he was right. Revenue Operations is a vocabulary that describes the convergence of all the systems, operations and data that support the revenue cycle is happening. A third of organizations have announced a CXO, combining sales, marketing, and success, or some permutation.

We just did a profile on a wonderful gentleman who was brought in from Microsoft to transform Johnson Controls, a company I love. And he’s got one of the biggest CMOs in the world working for him and sales and customer success and all the technology that supports that because he’s trying to convert that into a SaaS company. So most people are doing that. 95% of people are trying to jam this tech stack together. We have an operating system for computers, for school use, for governments, for anything complex in the world as an operating system, except for sales and marketing. And there’s enough moving parts and enough complexity that it’s time. A PC wouldn’t work without an operating system. Nor would heating, ventilating, and air conditioning. And it’s time for us to have that.

And so I don’t know how we got to the naming thing, but I called it the 21st Century Commercial Model. And of course, that’s a horrible name. But if you think about we’re running businesses using a 20th Century commercial model, that we’re assuming it’s Mad Men in advertising and lips.

Betsy Peters: Yeah, no.

Stephen Diorio: We don’t account for the fact that the majority of the investment supporting sales is technology, not media, not human beings. And I think it’s a timely book. It’s a bit egghead-ish, but its goal is to convince people to change, not to be a good airplane read.

Betsy Peters: Yeah, that’s great. I can’t wait to read it and I will definitely put it in our show notes.

What we try to do with the last question is say, if there is a young person who’s interested in entering into RevOps, what do you recommend? What do you think they should be studying? Who should they be following? What should they be reading, other than your great book? What are some good recommendations for somebody who’s entering the field?

Stephen Diorio: I am super excited about this. I got three vectors. One, Bob Liodice, who runs the ANA, the biggest advertising organization, said, “If you want a career in marketing, you need to understand RevOps.” I also have the Dean of Wharton Business School saying, “We have failed a generation of talent by teaching aspects of the growth formula, but growth is interdisciplinary.” You need to understand brands, finance, analytics, and sales, which most business schools don’t teach. And so it’s an interdisciplinary skill that leads you to the C-suite.

So what would a young person do? Well, I’ll tell you the story of my awesome nephew, Michael. Michael was a D1 athlete, a really good pitcher, competitive, charming, good-looking. But, like a lot of kids. He wound up in a call center job, and he figured it out. He was an athlete, he rang the bell by treating customers right, and he figured it out. But he became a CRM administrator and he got his hands … And again, the salespeople make all the money. The sales guy used to become the CEO of the company. The sales guy used to become the chief revenue officer.

Well, he gets his hands dirty in the data. He’s quickly become the most important person in his firm, because he knows where the bodies are buried. He can pull the data together. He knows what it’s telling you, what it’s not, how clean it is. And he’s learned the language of finance. He is making his way into the boardroom because he’s the only person who can incredibly explain the data that the CRO can’t. The CFO can’t. The IT people can’t. But he’s talking to the salespeople. He’s forcing people to put things into CRM. He’s using Salesforce to its maximum. He’s cleaning it up, but he’s so deep in the data that he’s actually on his way to the C-suite.

And I think that’s what I’ve heard people say is the next generation of sales leaders, or even these CXOs who are the top growth person in the company, much less the CEO, is going to have to understand the analytics, going to have to understand this revenue cycle, have to understand data and speak finance. And I would advise people to understand those things. Now, some of them are in the book. We’ve given you a mechanism to speak to finance. We’ve given you a coherent way to think about how these pieces come together. But I’m very convinced, and I’m seeing it with my own eyes. In fact, we call these guys RevOps superstars, and no executive will even tell me their name because they think I’m going to go on a podcast and mention their name, and someone’s going to steal them. And they’re like, “I couldn’t do my job without this person.”

So I think it’s a huge career path. But you got to think about it as being a CRM administrator was not a glamour job 10 years ago. Now I’m arguing it’s the pathway to a CEO.

Betsy Peters: Interesting. That is an awesome quote right there. And good to get people thinking in those directions, especially young people. We did a little bit of background research on you, and on Wikipedia it shows you are the inventor of beer pong. So we had to close off by asking that question. Is it first of all fact or fiction?

Stephen Diorio: According to Wikipedia and the editor of my college newspaper, I am. And I would encourage everyone to go see that picture because you’re going to see that John McEnroe afro with the headband.

Betsy Peters: Well, terrific. It’s also another good illustration that you don’t have to be an egghead to be in CRM and in RevOps. So anything that we didn’t ask that you’d like to leave the podcast on, Stephen?

Stephen Diorio: No, I think you nailed it. And I’m really glad you got to the career path aspect to this because growing a business is interdisciplinary. And it kills me, I’ll talk to the CMO, and they whine to me that people don’t understand the value of the brand or which is valuable. And I talk to people in sales and people don’t … And they may complain to me about other things.

And I think the fact of the matter is … Or the finance people don’t appreciate them. I think you’ve got to learn this lingua franca, and you’ve got to learn how all these things come together around the customer lifetime value. And any effort to do that and communicate that and quantify that will be a productive endeavor.

Betsy Peters: Yeah, and it comes back to the beginning of the interview where you were talking about systems thinking. That’s what this is. It’s really thinking of this holistic customer journey as a system and how we all map up against it and play the game for the greatest value, for the customer and for ourselves.

Stephen Diorio: Well, that was a pretty intense interview.

Betsy Peters: Well, I hope I didn’t wear you out. I’m sorry. It’s just such a treat to have someone who has so much experience and such deep thought about all this stuff, so I really very much appreciate your willingness to play full out for an hour.

Announcer: Thank you for tuning into the Rev-Tech Revolution Podcast. If you enjoyed this episode, please don’t forget to rate, review and share this with colleagues who would benefit from it. If you’d like to learn more about how Riva can help you improve your customer data operations, check out rivaengine.com.